PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL DOCTRINE UNDER AUSTRALIAN LAW AND SUGGESTIONS TO IMPROVE VIETNAM’S LAW ON THE FORM OF REAL ESTATE BUSINESS CONTRACTS TO PROTECT THE RIGHTS OF REAL ESTATE BUYERS

PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL DOCTRINE UNDER AUSTRALIAN LAW AND SUGGESTIONS TO IMPROVE VIETNAM’S LAW ON THE FORM OF REAL ESTATE BUSINESS CONTRACTS TO PROTECT THE RIGHTS OF REAL ESTATE BUYERS

Nguyễn Song Ngọc Chung

Master of Law, Faculty of Law, Saigon University

Cao Văn Hải

Bachelor, Uni Export Company Limited

ABSTRACT

This article outlines the form of contracts related to real estate under Australian and Vietnamese law, focusing on the legal consequences of violating form regulations according to the laws of the two countries and the promissory estoppel doctrine under Australian law. It aims to propose some suggestions to improve Vietnam’s law on the form of real estate business contracts to protect the rights of real estate buyers.

Keywords: form of contract, protection of the rights of real estate buyers, promissory estoppel doctrine

I. INTRODUCTION

The 2014 Law on Real Estate Business has addressed most issues related to the real estate business sector, contributing to the creation of a transparent, healthy, and sustainable real estate business environment. It maximizes convenience for investors, businesses, and individuals to access diverse real estate, meeting the needs of business, use, and practical life services. However, alongside the achievements, there remain existing problems and challenges that create difficulties during implementation. These issues necessitate amendments and supplements to the legal regulations to ensure they meet the practical requirements of real estate business activities and align consistently with newly enacted or upcoming laws.

Based on this, the 2023 Law on Real Estate Business was enacted to overcome the limitations and shortcomings of the 2014 Law on Real Estate Business. Notably, the 2023 Law on Real Estate Business includes many new provisions aimed at protecting the rights of real estate buyers, such as capping the deposit amount at no more than 5% of the future housing sale price, reducing the prepayment amount for leasing future housing, and adding many important legal concepts related to real estate business and real estate business contracts.

However, the 2023 Law on Real Estate Business still distinguishes between real estate business contracts where the parties are individuals and those where one party is a real estate business enterprise. Consequently, when one party is a real estate business enterprise, notarization and authentication are not mandatory.

This can disadvantage individual real estate buyers as not all individuals possess adequate legal knowledge and the ability to verify records, procedures, business conditions, and the capabilities of the investor. Conversely, when individuals are parties to the contract, notarization and authentication are mandatory; if the form of the contract is violated, the contract may be rendered invalid. This contradicts the principles of freedom and voluntariness in civil law, allowing one party to exploit this regulation for unjust gain.

To contribute to the improvement of the law on this matter, this article analyzes several provisions of Australian law related to the form of real estate business contracts as a basis for proposing solutions.

II. FORM OF REAL ESTATE BUSINESS CONTRACTS UNDER AUSTRALIAN LAW

- General Overview

According to Australian law, contracts can be made orally, in writing, or even implicitly through the actions of the parties. Generally, parties are free to choose the form of the contract according to their actual needs. For simpler contracts such as everyday civil transactions, parties often opt for oral contracts. Conversely, for high-value, complex transactions, parties will choose written contracts because, in addition to recording the rights and obligations of the parties, written contracts can also be easily used as evidence in case of disputes. The form of written contracts is also diverse: it can be as simple as a handwritten document with the signatures of the parties or more complex in the form of a deed.

However, in some cases, the law requires that contracts must be made in writing. Specifically, for transactions related to real estate, the parties must make contracts in writing, with the signatures of the parties, and may be “sealed” (Clive, John & Roger, 2021). The mandatory requirements for the form of contracts related to real estate serve two purposes: evidentiary purpose and cautionary purpose.

Firstly, creating a written document serves to prove the existence of the agreement between the parties, recording the rights and obligations of the parties through the contract terms, and contributing to ensuring legal safety in transactions. The specific and clear written record of the rights and obligations of the parties can help limit breaches of obligations or disputes over the contract. Additionally, a written contract also provides the court with accurate and convincing evidence during litigation in case of disputes.

Secondly, transactions related to real estate are often high-value transactions and may represent an individual’s entire assets. Therefore, the requirement for real estate-related contracts to be in writing is seen as a warning about the importance of this type of contract, prompting the parties to think carefully before entering into an agreement. Not only does it encourage the parties to think carefully before participating in the transaction, but the requirement for the form of the contract also aims to enhance caution in drafting the contract, avoiding mistakes due to careless use of language (Fuller, 1941).

- Legal Consequences of Violating Contract Form and Promissory Estoppel Doctrine

In most Australian states, contracts related to real estate must be made in writing. Specifically, Australian law stipulates that “… no action shall be brought upon any contract for the sale of … unless the contract or some note or memorandum thereof is in writing, and signed by the party to be charged …” (Civil Law (Property) Act 2006 – Sect 204(1)). This provision has historical roots in the Statute of Fraud enacted in England in 1677. Specifically, this statute required that certain important contracts, such as those related to land, be made in writing to provide the court with appropriate evidence to ensure the enforcement of the contract in the event of a dispute (Hugh, 2010).

However, the phrase “no action shall be brought upon any contract for the sale” does not mean that the contract is “invalid” but simply that in the event of a dispute, the parties cannot rely on the contract to prove their rights and obligations, and the court will not protect the rights and interests of the parties according to the contract terms (contract is “unenforceable”).

For instance, if the parties only make an oral agreement for the sale of land, the oral contract between them is “unenforceable,” and the court will not use the contract to resolve any disputes. However, if the buyer has paid a deposit but fails to complete the payment, the seller is entitled to keep the deposit, even if there is no written contract between the parties (Thomas v Brown (1876)).

Additionally, Australian law still protects the rights of the parties under the doctrine of “part performance.” According to this doctrine, if one party has substantially performed their obligations under the contract, the contract will remain enforceable, even if it does not meet the form requirements (Clive, John & Roger, 2021).

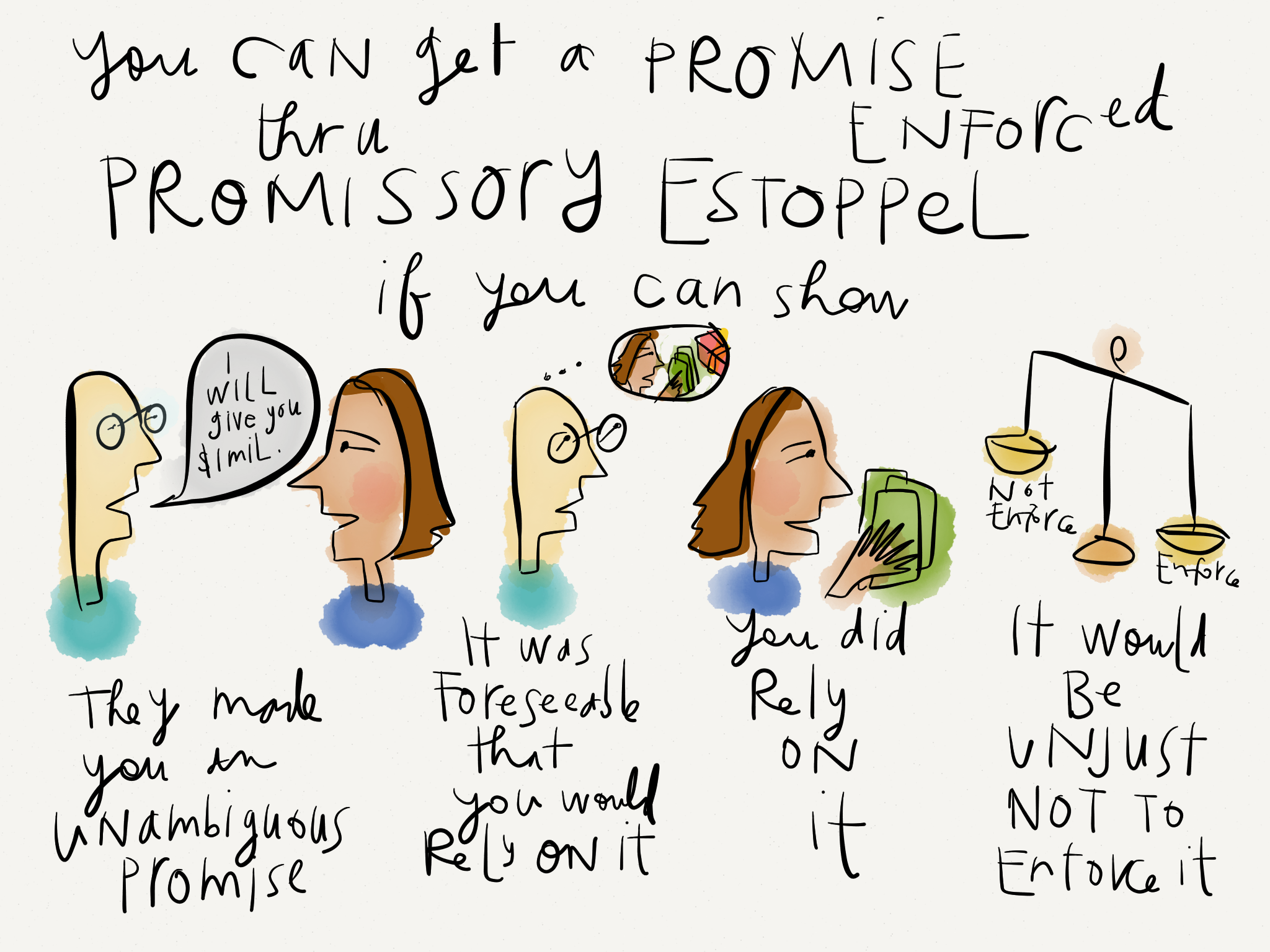

In addition to the doctrine of “part performance,” Australian law also applies the doctrine of “promissory estoppel” to real estate-related contracts that violate form requirements or to situations where the parties have agreed to sign a contract but have not completed the proper procedures. According to this doctrine, the commitments of the parties will still be recognized if six conditions are met: (1) one party makes a commitment, (2) the other party believes that there is or will be a contract between the parties, (3) the other party acts based on that commitment, and (4) damage occurs; (5) the committing party is aware of the other party’s actions but (6) does not prevent them (Clive, John & Roger, 2021).

For example, in the case of Sidhu and Van Dyke, Van Dyke rented a house from Sidhu and they developed a romantic relationship, leading to infidelity and ultimately Sidhu divorcing his wife. Sidhu promised to give Van Dyke the house they were living in. However, after eight years, when they broke up, Sidhu did not keep his promise. The court found that Van Dyke had relied on Sidhu’s promise, believing that there was a contract between them, which led her to agree to live with Sidhu in that house for an extended period. Therefore, the court protected Van Dyke’s rights even though there was no written contract between them (Sidhu v Van Dyke (2014)).

This doctrine of promissory estoppel is part of Equity law in England. Accordingly, if rigidly applying Common law could result in injustice, the court will use its discretion to apply equity to ensure fairness. Thus, the system of Equity law was formed, comprising a set of legal principles, doctrines, and remedies that supplement the strict rules of Common law (Catharine, 2021).

The promissory estoppel doctrine allows for the protection of a person’s rights based on reliance on another person’s promise, even if there is no legal guarantee, which can be understood as a way to ensure the fulfillment of promises even if the parties do not have a legally compliant contract (Lê, 2023). However, this does not mean that Australian law contradicts its own regulations regarding the form of contracts. Australian law still emphasizes the evidentiary function of written contracts. Accordingly, if a promise is important enough, it should be included in a written contract; promissory estoppel is only a last resort to protect the rights of the parties.

This perspective is demonstrated in the case between Crown Melbourne Ltd and Cosmopolitan Hotel (Vic) Pty Ltd (2016), where Crown Melbourne promised to prioritize the renewal of the real estate lease contract with Cosmopolitan Hotel but did not include it in the written contract.

Although the hotel invested a significant amount of money in the project based on this promise, the court held that the term “priority for contract renewal” did not equate to a commitment to renew the contract. Moreover, the parties to the contract had equal legal status and could have requested the other party to record the renewal agreement in writing. Applying promissory estoppel in this case would be an abuse and contrary to the equitable spirit of the doctrine (Clive, John & Roger, 2021).

Additionally, the promissory estoppel doctrine does not conflict with contract form regulations due to its principle of minimal remedy. This guiding principle aims to minimize damage and ensure fairness when applying the doctrine. For example, in the case of Waltons Stores (Interstate) Ltd and Maher (Waltons Stores (Interstate) Ltd v Maher (1988)), there was no written contract between the parties, although the law required construction-related contracts to be in writing. The value of this contract was significantly higher than the market value, so despite the application of promissory estoppel, Maher only received the market value instead of the agreed amount in the contract.

From the above analysis, it can be seen that, under Australian law, the requirement for real estate-related contracts to be in writing primarily aims to protect the rights and interests of the parties, provide evidence in case of disputes, support litigation processes by providing the court with appropriate and clear evidence, and contribute to ensuring legal safety in transactions.

III. FORM OF REAL ESTATE BUSINESS CONTRACTS UNDER VIETNAMESE LAW

- General Overview

Under Vietnamese law, parties are generally free to choose the form of their contracts, including oral contracts, written contracts, or specific actions; except for contracts where the form of the civil transaction is a condition for its validity as prescribed by law (Clause 2, Article 117 of the 2015 Civil Code). For instance, contracts for the sale of housing (Article 430 of the 2015 Civil Code and Article 164 of the 2023 Law on Housing) or contracts for land use rights (Article 502 of the 2015 Civil Code).

When the form of a contract is violated, the contract is invalid, except in cases where:

(1) A civil transaction required by law to be in writing but the writing does not comply with legal regulations, and one or both parties have performed at least two-thirds of their obligations, the court, at the request of one or both parties, shall recognize the validity of the transaction;

(2) A civil transaction is in writing but violates mandatory notarization or authentication requirements, and one or both parties have performed at least two-thirds of their obligations, the court, at the request of one or both parties, shall recognize the validity of the transaction. In this case, the parties do not need to perform notarization or authentication (Article 129 of the 2015 Civil Code).

However, the determination of what constitutes the performance of at least two-thirds of the obligations in the transaction is not clearly specified. In practice, obligations may be asset-related (payment in money or kind) or non-asset-related (performing transfer procedures). For asset-related obligations, it is easy to measure two-thirds of the obligations. But for non-asset-related obligations, there is no clear basis for determination (Trịnh, 2020).

- Form of Real Estate Business Contracts

The 2023 Law on Real Estate Business stipulates that: “A real estate business contract is a written agreement between real estate business organizations or individuals qualified under this Law and other organizations or individuals for the purposes of selling, leasing, leasing-purchase of houses and construction works; transferring, leasing, subleasing land use rights with infrastructure in real estate projects; or transferring all or part of a real estate project” (Clause 8, Article 3 of the 2023 Law on Real Estate Business).

In addition to the requirement for contracts to be in writing as prescribed by the Civil Code, the 2023 Law on Real Estate Business adds further notarization and authentication requirements: “Sales, lease-purchase contracts of houses, construction works, or floor space in construction works where the parties involved are individuals must be notarized or authenticated” and “Real estate business contracts, real estate service contracts where at least one party involved is a real estate business enterprise shall be notarized or authenticated at the request of the parties” (Clauses 3 and 4, Article 44 of the 2023 Law on Real Estate Business).

If we consider the form of the contract as a legal corridor to protect the rights of the parties involved and to support the litigation process by providing specific, clear, and appropriate evidence as analyzed above, then the distinction between individuals and real estate business enterprises is unreasonable.

While real estate is a significant and valuable asset for people, the legal documents related to real estate products of real estate business enterprises are often very complex, and not everyone has the ability to verify records, procedures, business conditions, or the capabilities of the investor. This presents a potential legal risk for homebuyers, as evidenced by the fact that in disputes, homebuyers are always the weaker party. Therefore, notarization in this case plays a role in control, warning, prevention, and risk mitigation for the public (Government Electronic Newspaper, 2023).

Conversely, if the form of the contract is viewed as a legal corridor to protect the rights of the parties involved and to support the litigation process, the provision that a contract is invalid if it violates form conditions is unreasonable. For instance, in the case of Mr. Phan Q. and Mr. Lê Văn D. in Judgment No. 621/2020/DS-PT on July 1st, 2020, by the People’s Court of Ho Chi Minh City regarding the dispute over land use rights. Mr. Phan Q. transferred the land to Mr. Lê Văn D. in 2002 using a handwritten document.

By 2011, the parties had completed the payment obligations, and Mr. D.’s family moved to the land. In 2017, Mr. Q. sued, claiming that the sale was invalid because it was only documented by hand and not notarized or authenticated. The appellate court accepted Mr. Q.’s lawsuit entirely, declaring the transaction invalid. Thus, in this case, the contract form provision not only failed to protect the buyer’s rights but also became a tool for the seller to unjustly profit.

Another example of the inadequacy of declaring contracts invalid if they violate form conditions: According to Judgment No. 20/2015/KDTM-ST on April 15th, 2015, by the People’s Court of Tân Bình District regarding the dispute over a house lease contract. The house lease contract was in writing but was not notarized or authenticated. Since the lease term agreed upon by the parties was 5 years, the contract required notarization or authentication and registration according to Article 492 of the 2005 Civil Code. Therefore, the house lease contract was invalid in form. Once again, declaring the contract invalid due to form violation contradicts the freedom of will of the parties and does not align with the parties’ interests.

Through the above analysis, it is undeniable that mandatory regulations on the form of contracts, especially the role of notarization and authentication, are crucial in protecting the rights and interests of citizens. However, the current regulations on the legal consequences of violating contract form requirements still have inadequacies, not fully aligning the principle of freedom of will with the protection of parties’ rights and enhancing state management.

IV. SUGGESTIONS

Some proposals to improve the law on the form of real estate business contracts are as follows:

Regarding the regulation of notarized and authenticated documents as a statutory form for some real estate-related contracts. Most transactions related to real estate are complex and can give rise to numerous disputes over the rights and obligations of the parties.

The form of notarized and authenticated documents, with the participation of notaries who are knowledgeable in law, will be an effective measure to protect the rights of the parties and ensure the cautionary and evidentiary functions mentioned above, especially in transactions where one party is an individual whose legal understanding is significantly lower compared to a real estate business enterprise. Therefore, to protect the rights of real estate buyers, notarization and authentication should be mandatory for transactions between individuals and real estate business enterprises.

However, rigidly declaring contracts invalid if they violate form conditions does not ensure the principle of freedom of will of the parties and creates loopholes for one party to unjustly profit. On the other hand, the 2015 Civil Code’s provision for exceptions when one party has performed at least two-thirds of their obligations in the transaction aims to limit cases where one party does not act in good faith and cites form violations to void the entire transaction when the contract value fluctuates (Ministry of Justice, 2017).

Additionally, Precedent No. 55/2022/AL on recognizing the validity of contracts violating form conditions has even developed towards expanding the scope, allowing this provision to apply retroactively to transactions arising when the 2005 Civil Code was in effect. This can be seen as a basis for applying fairness. However, the current approach remains quite rigid, requiring proof that one or both parties have performed at least two-thirds of their obligations (Đỗ, 2023).

Meanwhile, applying the promissory estoppel doctrine similar to Australian law would provide more flexible legal remedies for form condition violations. This doctrine allows consideration of the nature of each specific case. The primary purpose of this doctrine is to limit cases where one party does not act in good faith and cites form violations to void the entire transaction when the contract value fluctuates; fully aligning with the spirit of the 2015 Civil Code.

V. CONCLUSION

Although the 2023 Law on Real Estate Business has introduced many new provisions aimed at protecting the rights of real estate buyers, the distinction between notarization and authentication for contracts involving individuals versus those involving real estate business enterprises may disadvantage individual real estate buyers. Additionally, the provision that form violations can render contracts invalid contradicts the principle of freedom and voluntariness in civil law, allowing one party to unjustly benefit from this regulation. To contribute to improving the law on this matter, the article has analyzed some provisions of Australian law and proposed several solutions, including the application of the promissory estoppel doctrine as a solution that aligns with the spirit of Vietnamese law.

REFERENCES

- Government Electronic Newspaper. (2023). No notarization of real estate business contracts: More worry than relief. Retrieved from https://baochinhphu.vn/khong-cong-chung-hop-dong-mua-ban-bat-dong-san-mung-it-lo-nhieu-102230217185029439.htm

- Ministry of Justice. (2017). New points of the 2015 Civil Code. Labor Publishing House;

- Catharine, T. (2021). The Function of Equity in International Law. Oxford University Press;

- Clive, T., John, T. & Roger, G. (2021). Concise Australian Commercial Law. Lawbook Co.;

- Đỗ, G. N. (2023). Form of real estate-related contracts in some countries around the world and policy implications for Vietnam. Legislative Research Journal, 12 (484);

- Fuller, L. (1941). Consideration and form. Columbia Law Review, 41(5);

- Hugh, B. (2010). Cases, Materials and Text on Contract Law. Oxford: Hart Publishing;

- Lê, T. D. P. (2023). Applying Equity in Dispute Resolution in Some Countries and Lessons for Vietnam. Procuracy Journal, 14/2023.

- Trịnh, T. A. (2020). Invalid contracts due to non-compliance with form regulations – Current situation and solutions, Electronic People’s Court Journal. Retrieved from https://tapchitoaan.vn/hop-dong-vo-hieu-do-khong-tuan-thu-quy-dinh-ve-hinh-thuc-thuc-trang-va-huong-hoan-thien

If you need more consulting, please Contact Us at NT International Law Firm (ntpartnerlawfirm.com)

You can also download the .docx version here.

“The article’s content refers to the regulations that were applicable at the time of its creation and is intended solely for reference purposes. To obtain accurate information, it is advisable to seek the guidance of a consulting lawyer.”

LEGAL CONSULTING SERVICES

090.252.4567NT INTERNATIONAL LAW FIRM

- Email: info@ntpartnerlawfirm.com – luatsu.toannguyen@gmail.com

- Phone: 090 252 4567

- Address: B23 Nam Long Residential Area, Phu Thuan Ward, District 7, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam